There is something very satisfying about pulling weeds. Especially when the soil is moist but not too wet. Sometimes, if you get a good grip on the base of the stem and apply just the right amount of pressure, the whole root system comes out in one piece. It doesn’t happen like that very often, but when it does, I marvel at the complexity of the root system – reaching and branching and spinning off a host of smaller hairlike roots, so fine as to be nearly indistinguishable from the soil itself. So when I say that my mother’s death in July felt like something essential was uprooted in me, I mean this in a very literal way.

The person I am, and the life I have now is all built upon the root structure that she provided. Her values and priorities became my foundation, her voice became my inner voice. Her fierce positive attitude, easy laugh, love of reading, penchant for animals and young children, even her recipes – are all mine now.

As she gradually got sicker, balances shifted. The meals she used to cook and the gatherings that she used to host became mine. She had less energy to engage. Her world and her roots got smaller. I felt the inexorable withdraw of her presence, as she had less and less to give. Then this summer, she was gone. All of the times and places I had always found her – phone calls in the car, notes and small treasures saved up for me in blue plastic bags, quick consults about family and food and current events – they abruptly ended. Those spaces were all empty now. She was uprooted from my heart. Like the soil left behind after weeding, the ground of my life was disturbed. I felt disoriented. Fragile. Full of gaps and holes. Prone to sudden and unexpected collapse. It was hard to find my footing in the new landscape, without her.

I was lucky though. Tended by family, friends, held by the rituals of grief, over the months we built new structures and routines. Daily phone conversations with Dad. Stronger connections with my brothers. More intentional planning to gather and spend time. Grief refit the pieces of my life back together in new ways.

But I was worried about Christmas. She loved so much abut it – the decorating, finding and wrapping gifts, cookies, music, the food, family time, right down to the annual gag gifts from the dollar store. I felt raw again in December, thinking of her absence from every bit of the holiday. I was scared by what I would feel and whether it would hurt too much to bear.

I was surprised. Certainly, I miss her fiercely. It’s hard to count the number of times I thought of her, of what she would have done or said, of how much she would have loved this or that. But it felt more gentle than I expected. A lifetime of living with cracks and broken places had prepared me to bear the loss with care and patience. The fissures of grief were not only wrenching and empty and lonely; there was also gratitude and joy.

Over the years I’ve practiced many ways of living with empty, broken places. I know what it is to carry the sharpest bits in my hands, to feel the bite of pain in every breath. I know how to breathe through pain, to let the waves of feelings crash and break and recede. I know how to slow down, to rest and take breaks, to loosen my grip and make a little room. And I know that healing and moving forward is not about forgetting or abandoning the past. There are many ways to bear brokenness that cannot be mended.

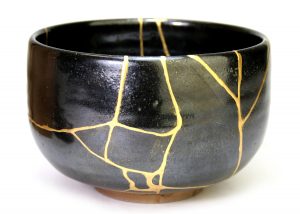

There is a Japanese practice of mending broken pottery, using gold to fill in the cracks. Called kintsugi, it treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. This seems right and fitting to me as a metaphor for grief and healing – to find ways to fill in the cracks and broken places with love.

Merry Christmas, Mom. I love you.

Living with the cracks and broken places

Back to News